“Sitting is the new smoking.” Those words have taken shape in headlines, articles, and blog posts, highlighting the dangers of a sedentary lifestyle. Being sedentary doesn’t show its teeth early on, but over the course of years, the body begins to adapt to this lifestyle. Muscles get tighter and lose flexibility, joints lose their range of motion and become painful to move. Meanwhile, rest and exercise-avoidance is the natural response and it later becomes normalized. Over time, the systems of the human body no longer experience the amount of physical movement necessary to keep its functional integrity. As a result, systems begin to fail. After decades of spending time in the chair, it’s time to take a stand.

When we think about adopting an active lifestyle, exercise often comes to mind. On the other hand, it is also the last thing on our mind. One hour of exercise would typically account for approximately 6.25% of the day, assuming that we should be having 8-hours of sleep. A mere 6.25% of the day cannot reverse the effects of being sedentary for the remaining 93.75% of the day. Our bodies adapt to our most common activity—sitting—and that’s why exercise alone is just a fraction of the solution.

Physical activity is recognized as one of the 4 pillars of obesity medicine by the Obesity Medicine Association. Exercise is not at the absolute forefront, but instead exists as a subcategory of physical activity. It is crucial to recognize that physical activity encompasses more than just exercise and can have a much larger impact on our lives. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) is a vital component of physical activity that deserves our attention.

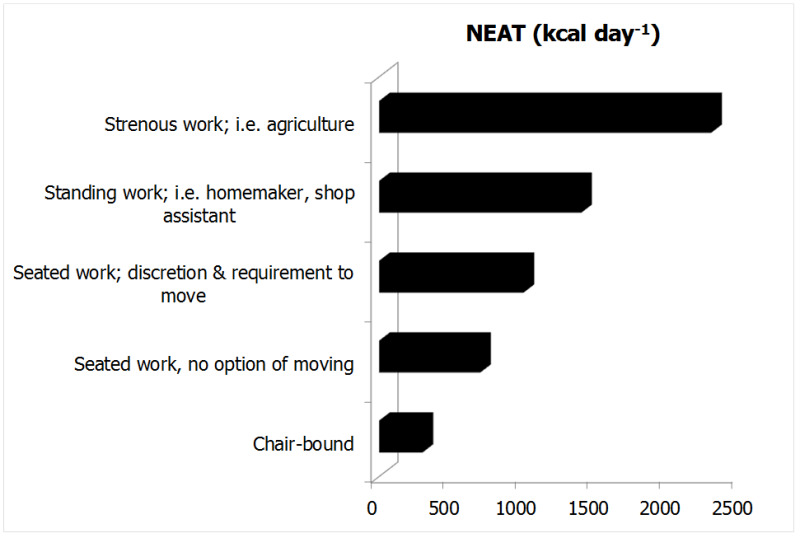

NEAT is the energy we expend through movement that does not include eating, sleeping, or structured exercise. Examples of NEAT would include things like walking, fidgeting, cooking, taking a shower, and scaling stairs. Movement created by our muscles requires energy, which is why we “burn” energy when we move. While one hour of exercise can burn approximately 200-600 calories depending on type and intensity, NEAT has the potential to utilize up to 2000 calories in a day (Levine, 2007). Exercise tends to hog the spotlight, but the amount of day-to-day activities we participate in or NEAT has a profound impact on our total daily energy expenditure, which is meaningful for weight loss and preventing weight regain.

At Enara, we use the metabolic test to measure the resting energy expenditure (REE), which is the amount of energy the body utilizes at rest. On our metabolic test results, exercise and lifestyle and activity are estimated into the calculation for one’s total energy output, or total energy expenditure (TEE). The TEE can increase or decrease depending on the amount of NEAT that takes place. For an individual that has a lower REE and wishes to increase their TEE, increasing NEAT is the easiest thing to do because it is effective immediately and it can be done anywhere!

Here are 10 examples of how to increase NEAT:

- Walking or bicycling instead of taking a car or bus.

- Taking the stairs instead of the elevator.

- Using a standing desk and or an under the desk treadmill or peddler.

- Walking or pacing back and forth while on calls.

- Balancing on one leg while waiting in line.

- Parking further away from your destination.

- Setting timers to take breaks from the desk.

- Performing active house chores.

- Standing while reading or walking with an audio book.

- Watching TV while on a stationary bike or treadmill.

If you’re interested in tallying up how much NEAT contributes to your total energy expenditure, try this!

This graphic demonstrates how significant NEAT’s role is in calorie expenditure!

The clinical implications of NEAT on obesity are well described in the research. As mentioned earlier, the body adapts to one’s lifestyle and those adaptations take shape over time. NEAT and adiposity have an inverse relationship (Zhu et al., 2020). More NEAT means less adipose tissue. A 2006 study by Levine et al. found that individuals with higher levels of NEAT experienced greater weight loss and maintained their weight compared to those with lower levels of NEAT. Additionally, a 2015 study by Drenowaltz et al. concluded that individuals with high levels of NEAT were met with successful weight maintenance.When reviewing studies of the effect of NEAT on cardiovascular health, Ekblom-Bak et al. (2014) found that higher levels of NEAT reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease events by 27%! Prioritizing NEAT to adopt an active lifestyle has been shown to improve health outcomes and it’s done by just moving more.

NEAT holds immense potential for those embarking on a sustainable journey towards improved health. By understanding the value of NEAT and its impact on energy expenditure, individuals can generate a sustainable environment to which weight maintenance is manageable and mitigates weight regain. Incorporating daily practices that increase NEAT will yield gradual, but long-term health improvements that supplement an individual’s existing efforts towards improving weight, cardiovascular health, and general health. If you would like to learn more or discuss strategies to fit NEAT into your day, reach out to your exercise specialist. Whether you are at home, at work, or out and about, stand up for yourself and your health!

References

- Ekblom-Bak, E., Ekblom, B., Vikström, M., Faire, U.D., Hellénius, M.L. (2014). The importance of non-exercise physical activity for cardiovascular health and longevity. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(3):233-238. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/48/3/233.long

- Drenowatz, C., Hand, G. A., Sagner, M., Shook, R. P., & Burgess, S. (2015). The association between physical activity and weight maintenance in the ‘non-exercise’ activity thermogenesis (NEAT) era. International Journal of Obesity, 39(9), 1311-1317.

- Levine, J. A., Vander Weg, M. W., Hill, J. O., & Klesges, R. C. (2006). Non-exercise activity thermogenesis: The crouching tiger hidden dragon of societal weight gain. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 26(4), 729-736. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16439708/

- Levine, J. A. (2007). Nonexercise activity thermogenesis—Liberating the life-force. Journal of Internal Medicine, 262(3): 273-287. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17697152/

- Zhu, W., Cheng, Z., Howard, V. J., Judd, S. E., Blair, S. N, Sun, Y., & Hooker, S. P. (2020). Is adiposity associated with objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviors in older adults? BMC Geriatrics, 20, 257. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.atv.0000205848.83210.73