Key Takeaways

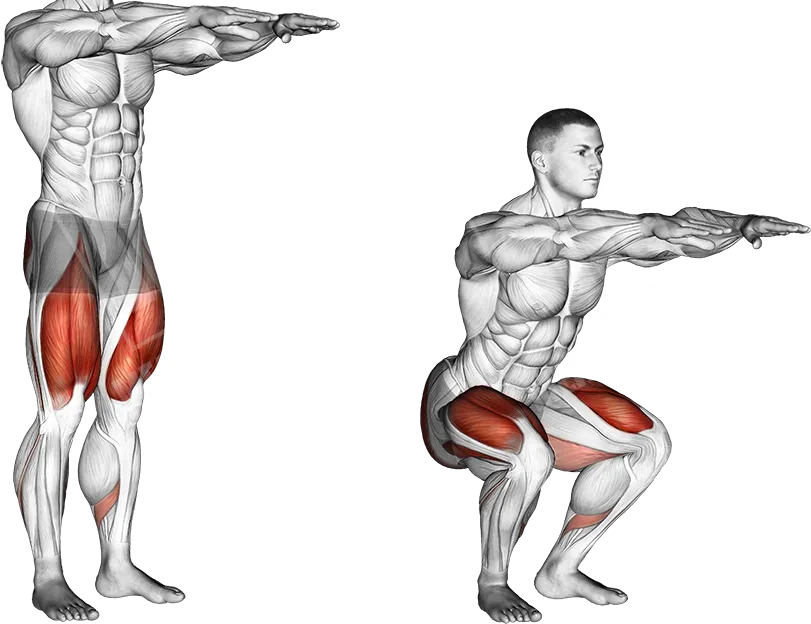

- Squats exercise all of the leg muscles, primarily the quadriceps and gluteus maximus.

- It is performed by keeping the heels grounded, bending the knees, lowering the hips, and leaning forward no more than 45 degrees.

- Flexibility in the hip flexors and calves, while strength in the low back and glutes are required.

Introduction

The squat is one of the most fundamental bilateral movements used in everyday life and exercise. This movement requires coordination, flexibility, and strength from the entire body. The absence of one of these key components will result in unfavorable variations in the biomechanics of the movement. Here, I will discuss the proper squatting technique, progressions, variations, and common technical errors. The learning objective is to learn to squat with purpose and to understand the biomechanics behind the movement.

Muscles Involved

The primary muscles driving the movement of the squat include the gluteus maximus and quadriceps. The gluteus maximus is known as the butt muscle and the quadriceps are known as the muscle in front of the thigh. During the squat, the gluteus maximus is responsible for hip extension and external rotation. The quadriceps are responsible for hip flexion and knee extension. Alongside these muscles are many stabilizing muscles that support the gluteus maximus and quadriceps throughout this movement. These involve the hamstrings, glutes, adductors, abductors, calves, and more.

Quadriceps:

Gluteus Maximus:

Variations due to Anatomical Differences

Squat technique is variable depending on the individual performing the movement. This is because everybody has slightly different anatomy. Some individuals have longer or shorter limbs, torsos, femurs, etc. that makes them squat differently than others. Changes to one’s squatting technique due to an individual’s skeletal anatomy is acceptable, but is not to be mistaken with the lack of flexibility, which is largely due in part to the muscles. In the next section, we will go over the starting position of the squat.

Position

In preparation for the movement, the squat begins in the standing position. The feet should be shoulder width and the toes out at approximately 11 and 1 o’clock. The weight distribution of the feet should be even between the ball of the big toe, ball of the little toe, and the heel. The low back should be straight and the muscles surrounding the abdominal region should be engaged. Squeezing the muscles from the abdominals in the front, obliques on the side, and low back muscles in the back aids in supporting the lumbar spine throughout the movement. Be sure to continue breathing, while focusing on keeping these muscles engaged. Stand tall so the chest is out and shoulder blades pushed down and pinched together. Lastly, tuck the chin back to keep the cervical spine in the neutral position.

Action

The speed at which the squat is performed is essential to ensure proper muscle engagement. It is important to focus on the fact that this is an exercise, which the goal is to strengthen the leg muscles. It is very easy to drop straight down into a squat because gravity will do the work, but doing so negates the purpose of squatting for exercise. Go slow on the way down and concentrate on engaging the correct leg muscles. Slowing down the movement increases the time under tension, which the muscles need to grow and get stronger.

The eccentric phase, or down phase, of the squat begins the movement. Focus on the hips. Lower the hips until they reach the depth of your knees. There should not be too much movement of the hips front to back. If there is a lot of movement, then an excessive forward lean of the torso is also likely. At the bottom of the squat, the torso should bend forward, but no more than about 45 degree angle. Everyone is built differently, so 45 degrees is not set in stone. The knees should point in the direction of the toes at all times and it is acceptable for the knees to extend past the toes, as long as the heels are able to remain grounded.

At the bottom of the squat it is important to focus on which muscles are being engaged. To ensure the correct muscles are engaged, push the three points in the feet into the ground. The quadriceps, glutes, and hamstrings should automatically engage. Pushing the feet into the ground also helps keep the center of gravity over the middle of the foot. The final step, at the bottom of the squat and before the up phase, is to push the knees out very slightly. Think about moving them apart 1 millimeter. This will engage the glutes and lateral hamstrings, while also protecting your knees from knee valgus. Knee valgus is characterized by the collapsing of the knees towards the midline. When the knee is flexed to ≥30 degrees, the knee joint can only rotate internally 30 degrees and externally 45 degrees. Placing a valgus stress on a loaded knee can cause an injury. With the correct muscles engaged, the legs are now properly prepared for the up phase.

Coming out of the bottom, the up phase is fairly simple because all of the correct muscles are already engaged. Continue to drive the feet into the ground and make sure the knees do not move inward. The knees are most likely to move toward the midline in the early stages of the up phase, but as long as there is an effort to push them out slightly, the glutes and lateral hamstring muscles will do their job to avoid this. To complete the movement, return to the standing position with a slight bend in the knees and squeeze the glutes. The squat has now been completed.

Feel

The muscles that will be felt during the squat include the glutes, quadriceps, and hamstrings. The glutes, known as the butt muscle, are located at the buttocks. The quadriceps are located in the front of the thigh from the hips to just below the knee. The hamstrings are located behind the thigh from the sitting bone of the hip to just below the knee. It is also possible to feel the adductors, which are the muscles on the inside of the thigh from the hips to just below the knee.

Purpose

The purpose of the squat as an exercise is to strengthen the legs throughout the range of motion of the movement. Walking also works each of these leg muscles, but for a much smaller range of motion. This is important to note because the muscle fibers adapt according to each movement. If walking is the only form of exercise the leg muscles perform, then the muscles will only adapt specifically to that range of motion. When squatting, a fuller range of motion is performed, which causes the muscles in the leg to adapt and build strength within a larger range of motion. When looking at the activities of daily living, the range of motion in a squat is crucial. It is used for getting up and down from a chair, climbing stairs, getting in and out of a car, and lifting objects off of the ground. Walking does not prepare the muscles for these types of movements.

Squat Progressions

The assisted bodyweight squat (Figure A) is a great way to gain entry into the squat. It is performed by holding onto a sturdy object, such as a pillar or rail, and squatting. This enables the object to off-load a large majority of the body weight and also allows the arms to assist if needed. Ball wall squats (Figure B) are a great option to begin using more of the legs. These are performed using a stability ball, where the ball rests between the wall and the back of the body. Leaning back on the wall off-loads body weight and the ball acts as a wheel that allows the body to slide up and down the wall. The final progression is a sit-to-stand squat (Figure C). A sit-to-stand squat is a common starting point for most individuals. It requires a chair to which the exercise is performed by sitting and standing. What’s great about this exercise is that the height can be adjusted. Some find squatting very challenging or are finding it difficult to squat very far. A pillow or pad can be placed on the chair to allow progression into a squat to the depth of a standard chair (18”). When ready, adding weights to the squat is the next step.

Squat Variations

Beyond the above discussed squatting methods, the body squat is the next step, which can be made more challenging by adding weight. There are many variations of squats, each with their own purpose and target muscles. Though there are many more, the following are the most common types of weighted squats:

Back Squat

| Brief Description | Weight on the back |

| Equipment | Barbell |

| Purpose | General leg strength |

Front Squat

| Brief Description | Weight in front |

| Equipment | Barbell |

| Purpose | Emphasis on quadriceps and thoracic mobility |

Goblet Squat

| Brief Description | Non-barbell weight in front and less flexibility required |

| Equipment | Dumbbell, kettlebell, or medicine ball |

| Purpose | Same as front squat |

Sumo Squat

| Brief Description | Wide stance |

| Equipment | Barbell, dumbbell, kettlebell, or medicine ball |

| Purpose | Emphasis on glutes, adductors (inner thigh), and hip flexibility |

Checking Squat Technique

There are 3 common errors when performing the squat: rounding of the back, excessive forward lean, and knee valgus. An excessive forward lean can sometimes be corrected with cues. There is a misconception that the goal of a goblet squat is to lower the weight towards the ground; however, the focus should really be on the lowering of the hips. In other cases, the forward lean is likely to be caused by one or more of 4 factors. Weakness of the low back muscles, shortened hip flexors, shortened calves, or weakness of the glutes. Weakness of the low back muscles may lead to an excessive forward lean because the low back muscles, such as the erector spinae, are not strong enough to hold the body upright. Weakness of the glutes can also produce a similar result because they are responsible for hip stability.

There are many hip flexors responsible for performing hip flexion, which more-or-less means to raise the knee. The psoas in particular is a hip flexor that causes a lot of problems because it attaches from the lumbar spine to the femur, or low back to the leg. It is a very common lifestyle to be seated for a very large majority of the day. Over time, the psoas and many other muscles adapt by becoming shorter. The shortening of the psoas can be a cause of an excessive forward lean during a squat because the muscle pulls the lumbar spine and femur closer together, restricting hip extension. Regular stretching and changing lifestyle-habits, such as standing or walking more, can help mitigate and reverse this.

Another factor that can lead to an excessive forward lean may stem from the calves. The calves are a group of muscles that consist of the gastrocnemius and soleus, located behind the shin, between the knee and heel. These two muscles act as the first line of defense when it comes to shock absorption from ground reaction forces. If these muscles are shortened, dorsiflexion will be decreased. This means the ability to raise the foot up towards the shin will be limited. Typically, a functionally sound range of motion for the calves needs to be less than 90 degrees. The reason is that the more the calves are able to elongate, the greater the range of motion the calves have to absorb forces by decelerating. Think of the muscle as a spring. A longer spring will have more room to absorb forces compared to a shorter spring. The shortening of these muscles are a result of many potential factors, which for example include an achilles tendon repair, a sedentary lifestyle, and genetics. Without flexibility of the calves to absorb force, the force travels up the chain, forcing the quadriceps to take a blunt of the force.

The quadriceps are located in the front of the thigh, between the hip and knee. The quadriceps are the second line of defense. The quadriceps are powerful muscles capable of absorbing large amounts of force, which make them great for deceleration. It is important to note that the quadricep tendon extends over the patella or the knee cap, ultimately attaching onto the tibia, known as the shin bone. This is significant because every time the quadricep muscle contracts, it pulls on that tendon, creating pressure on the patella. This is where some individuals may run into knee pain. The moral of the story is that calf flexibility is an essential component of movement that can result in major impacts. When it comes to squatting, a decrease in calf flexibility means that the knees will be unable to translate forward, which is a requirement for proper squatting technique. As a result, the only way to squat is to drive the hips back and lean forward to bring the chest towards the ground. This leads to the excessive forward lean. If an individual with shortened calves attempts to squat upright, they will likely feel as if they were going to fall backwards.

The final common error during the squat is knee valgus. Knee valgus describes the position of the knees, where the knees move towards the midline. Squatting in knee valgus presents poor biomechanics because the knees can only rotate approximately 30-45 degrees, depending on the amount of knee flexion and direction of rotation. A valgus knee places the hip (thigh) into internal rotation and the tibia (shin bone) into external rotation. Applying a valgus stress on a loaded knee that is absorbing force applies an unfavorable stress on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Though the likelihood of an ACL injury during a controlled squat is highly unlikely, training the legs to move with good biomechanics is transferable to real-world applications. For this reason the knees must always travel in the direction of the feet to eliminate any torque on the knee joint. There are many factors that lead to a valgus knee, but weakness in the glutes tend to be a common muscular cause.

Conclusion

In summary, the squat is a fantastic exercise that challenges not only the leg muscles, but the entire body’s mobility. Everyone’s anatomy varies, which results in variations in squatting techniques. Generally, the focus should be on the lowering of the hips with an upright torso. The feet should remain grounded at all times and the knees should point in the direction of the feet. There are many paths to progression and squat variations to suit the needs of the individual. Schedule an appointment with an exercise specialist for guidance on movement technique, progression pathing, and squat variation selection. Exercise specialists can also perform assessments to determine readiness to squat from a mobility and strength perspective to improve your ability to move.